Articles

COUNTRY LIVING – Susie Gillespie, Weaver

Devon weaver Susie Gillespie turns her crop of home-grown flax into wonderful woven creations that mix the techniques of the past with a sense of contemporary artistry words by louise elliott photographs by alun callender, click here to read the full article

DEVON LIFE – Susie Gillespie, Weaver

Sitting at the loom in a light and airy studio, tucked away in an ancient Devon orchard, one could imagine that it is here that artist Susie Gillespie finds her inspiration. Her new workshop and studio has made the ideal space to house her loom and to display some of her stunning woven artworks. However far beyond this quiet valley, she has been influenced by the prehistoric use of nettle in Egyptian and northern European textiles.

Susie graduated with an M.A. from Winchester School of Art in textile design, and has lived on the outskirts of Paignton for the past ten years. There are a number of very talented weavers in the county so it was a pleasure to discover something quite unique in her work. The use of antique linen yarn, and nettle which she imports from the traditional spinners of the Himalayas gives rich texture and a subtle depth to her weaving.

Explaining her use of these unusual materials, Susie recalls her days of visiting museums where she began to appreciate the art that went into the making of prehistoric textiles. “I was moved in a way that was perhaps more than a purely aesthetic response as if the act of weaving and the hours that went into producing even a small amount of cloth still gave life to these fragments.”

“I began to understand how using hand-spun yarns such as linen and nettle could transform a piece into fine art. The filaments still seem to have life in them and give the cloth I weave the organic and tactile qualities I so admire in Coptic fragments and other early textiles.”

There are several types of nettle that have been used historically, examples of which can be found in museums around the world. Bohemia Nivea, a Chinese nettle, has been discovered to have been used for wrapping ancient Egyptian mummies and our native nettle, Urtica Dioica was widely used in northern Europe including the bronze age Danes. Susie uses the giant Himalayan nettle, Girardinia diversivolia, known as Allo whose long fibres lend themselves to productive spinning.

Even the linens used in her work have an unusual story. “I often found machine spun linen lifeless and was lucky to hear of a batch of hand-spun linen yarn found in a derelict French weaving shop. It is difficult to age but is probably more than a hundred years old. It has lost none of its weaving qualities and has a character and colour that make it seem alive to my fingers and wonderful to use in artwork.”

Always on the search for hand-woven threads Susie knows that spinning is hard and often unpleasant work. “Even in the Himalayas much of this is now mechanised, resulting in a fibre that has lost much of its organic nature and no longer gives the uneven effect produced by the hand-spun form. Fortunately I found a Sherpa who has sent me nettle spun by Nepalese women, who began the long process of preparing the giant stinging nettles by using their teeth to decorticate it. “

Watching Susie prepare the warp for her next piece one begins to appreciate the physical energy that goes into weaving and then becomes part of the story behind each piece. Having owned a number of looms over the years, Susie has now settled on the pine loom that dominates her Devon studio. “It’s a relatively large loom that enabled me to have a good tension in the fabric which is ideal for weaving with such traditional yarns.”

Standing in the workshop viewing these incredibly peaceful and beautiful weavings, I ask Susie to define the inspiration in her work: “I do collect ideas in my head but I really need to start weaving to begin to see the work shaping into a woven image. With my current work I had number of images of ancient stones in my mind; one was a photograph of a set of stone steps creeping up a Nepalese mountainside and another was based on my memories of visiting the Neolithic standing stones in Carnac, Brittany. With both of those images it is so much more than the rich texture and colour of the stones that I try to portray in my work – it is the historic atmosphere of these places and the lives that have touched these stones over many centuries.”

With such traditional and natural images inspiring her work, it is not surprising that Susie relies on a subtle and natural palette of colours. The decoration in her work does not depend on imagery so much as the surface qualities inherent in the weave and the character of the yarn. The resulting artwork has a very contemporary feel and one can picture it adorning the whitewashed walls of traditional Devon barns as well as the rooms of stylish apartments.

Notes:

Nettle:

Allo, Girardinia diversifolia, the giant Nepalese stinging nettle, occurs naturally in damp woodland above altitudes of 1500metres and grows to a height of 3 metres, much taller than our native nettles. The fibre is the longest known in plants and has a high tensile strength and water resistance.

Coptic Textiles:

Indigenous Egyptian weavers during the Late Roman/Early Byzantine era produced amazingly intricate textile art. The small tapestry and pieces were used to decorate tunics or ‘dalmatics’ and were woven in a combination of linen and wool. Some preserved in graves under extremely dry, sandy conditions, are now the earliest textiles available to collectors and museums, dating from the 4th and 5th centuries.

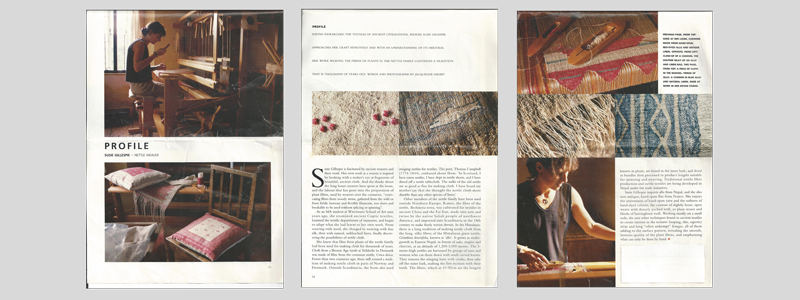

Gardens illustrated – Profile Susie Gillespie – Nettle Weaver

HAVING RESEARCHED THE TEXTILES OF ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS, WEAVER SUSIE GILLESPIE APPROACHES HER CRAFT SENSITIVLY AND WITH AN UNDERSTANDING OF ITS HERITAGE. HER WORK WEAVING THE FIBRES OF PLANTS IN THE NETTLE FAMILY CONTINUES A TRADITION THAT IS THOUSANDS OF YEARS OLD. WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHS BY JACQUELINE SARSBY

Susie Gillespie is fascinated by ancient weavers and their work. Her own work as a weaver is inspired by looking with a maker’s eye at fragments of beautiful, ancient cloth. And she thinks about the long hours weavers have spent at the loom, and the labour that has gone into the preparation of plant fibres, used by weavers over the centuries, “extricating fibres from woody stems, gathered from the wild or from fields; lustrous and flexible filaments, too short and breakable to be used without splicing or spinning”.

As an MA student at Winchester School of Art nine years ago, she examined ancient Coptic textiles, haunted the textile departments of museums, and began to adapt what she had learnt to her own work. From weaving with wool, she changed to weaving with fine silk, then with natural, unbleached linen, finally discovering the possibilities of nettle cloth.

She knew that fibres from plants of the nettle family had been used for making cloth for thousands of years. Cloth from a Bronze Age tomb at Voldtofte in Denmark was made of fibre from the common nettle, Urtica dioica. Fewer than two centuries ago, there still existed a tradition of making nettle cloth in parts of Norway and Denmark. Outside Scandinavia, the Scots also used stinging nettles for textiles. The poet, Thomas Campbell (1774- 1844), enthused about them: “In Scotland, I have eaten nettles, I have slept on nettle sheets, and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth. I have heard my mother say that she thought the nettle cloth more durable than any other species of linen”.

Other members of the nettle family have been used outside Northern Europe. Ramie, the fibre of the nettle, Boehmeria nivea, was cultivated for textiles in ancient China and the Far East, made into nets and twine by the native Salish people of northwest America, and imported into Scandinavia in the 18th century to make finely woven dresses. In the Himalayas, there is a long tradition f making nettle cloth from the long silky fibres of the Himalayan giant nettle, Girardinia diversifolia, also known as “allo”. It grows as undergrowth in Eastern Nepal, in forests of oaks, maples and cherries, at an altitude of 1,200-3,000 metres. The 3-metre-high nettles are harvested by groups of men and women who cut them down with small curved knives. They remove the stinging hairs with cloths, then take off the outer bark, making the first incision with their teeth. The fibres, which at 10-15cm are the longest know in plants, are found in the inner bark, and dried in bundles then processed to produce lengths suitable for spinning and weaving. Traditional nettle fibre production and nettle textiles are being developed in Nepal under fair trade initiatives.

Susie Gillespie imports allo from Nepal and she also uses antique, hand-spun flax from

France. She enjoys the unevenness of hand-spun yarn and the softness of hand-dyed colours, the contrast of slightly loose, open weave with densely packed weft, or plain weave and blocks of herringbone twill. Working mostly on a small scale, she uses other techniques found in ancient textiles to create interest in the texture: looping, slits, tapestry inlay and long “often unkempt” fringes, all of them adding to the surface pattern, revealing the smooth, lustrous quality of the plant fibres, and emphasising what can only be done by hand.

Digging Deep – Weaver Susie Gillespie draws the threads of the past together

Uncovering the past has always interested Susie Gillespie. As a student living in Oxford, her recreation time was spent volunteering on archaeological digs painstakingly recovering the past. Only the need for a chemistry qualification steered her away from a career in conservation but you could argue that Susie still works in the field. Her fascination with the study of past human societies through their material culture is expressed in works that embody a sense of early history and creativity with a power borne of simplicity.

With almost too much historical accuracy she was introduced to weaving by a Turkish boy whose family were traditional carpet makers. During a visit to Susie’s family he taught her how to weave on a simple frame. Despite a degree in Constructed Textiles and an MA from Winchester that followed, it is this formative experience that dominates and forms her pared down aesthetic.

Susie prefers antique linen or hand-spun unbleached yarn, “I often find machine spun linen lifeless and was lucky to hear of a batch of hand-spun linen found in a derelict French weaving shop it is difficult to date but is probably more than a hundred years old. It has lost none of its qualities and has a character and colour that make it seem alive to my fingers and wonderful to use,” explains Susie.

She also works extensively with nettles. The long fibres of the giant Himalayan nettle, Girardinia Diversifolia, lend themselves to spinning. It occurs naturally in damp woodland above altitudes of 1500 meters and grows to a height of three metres, much taller than native British nettles. The fibre is the longest known plant fibre and has a high tensile strength and water resistance. This unusual yarn is sourced for Susie by a Sherpa who buys it from Nepalese women. The spinners prepare the giant stinging nettles by using their teeth to decorticate it. The rich textures of these ancient fibres add depth to Susie’s weaving, reflecting her passion for prehistoric textiles. Each piece she makes is an intuitive personal journey, sometimes producing large full- loom width cloth or small fragmented pieces.

Her approach to weaving is quite at odds with the restrictive and measured nature of the measured nature of the process. The tactile surface qualities of her work do not depend on particular imagery but a visceral response to the surface qualities inherent in the yarn. The process begins with an idea but is shaped and developed instinctively on the loom relying on a subtle and natural palette of colours.

Susie finds inspiration in fragments of textile history such as Coptic textiles but her weaving contains other age-related influences. She finds beauty in ruins, the patterns in damp and crumbling plaster, the remains of paint on decayed wood, rotting bark and broken carvings.

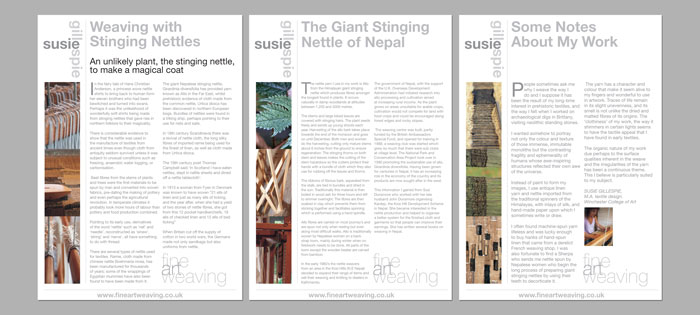

Weaving with Stinging Nettles

In the fairy tale of Hans Christian Anderson, a princess wove nettle shirts to bring back to human form her eleven brothers who had been bewitched and turned into swans.

Perhaps it was the unlikelihood of wonderfully soft shirts being made from stinging nettles that gave rise in northern folklore to their magicality. There is considerable evidence to show that the nettle was used in the manufacture of textiles from ancient times even though cloth from antiquity seldom survived unless it was subject to unusual conditions such as freezing, anaerobic water logging, or carbonisation. Bast fibres from the stems of plants and trees were the first materials to be spun by man and converted into woven fabrics, pre-dating the making of pottery and even perhaps the agricultural revolution. In temperate climates it probably took more hours of labour than pottery and food production combined. Pointing to its early use, derivatives of the word ‘nettle’ such as ‘net’ and ‘needle’, reconstructed as ‘sinew’, ‘string’ and ‘nerve’, all have something to do with thread.

There are several types of nettle used for textiles. Ramie, cloth made from chinese nettle Boehmeria nivea, has been manufactured for thousands of years; some of the wrappings of Egyptian mummies have also been found to have been made from it. The giant Nepalese stinging nettle, Girardinia diversifolia has provided yarn known as Allo in the Far East, whilst prehistoric evidence of cloth made from the common nettle, Urtica dioica has been discovered in northern European bogs. Bundles of nettles were found in a Viking ship, perhaps pointing to their use for nets and sails. In 18th century Scandinavia there was a revival of nettle cloth, the long silky fibres of imported ramie being used for the finest of linen, as well as cloth made from Urtica dioica. The 19th century poet Thomas Campbell said ‘In Scotland I have eaten nettles, slept in nettle sheets and dined off a nettle tablecloth’. In 1813 a woman from Fyen in Denmark was known to have woven “21 ells of linen and just as many ells of ticking, and the year after, when she had a yield of two stones of nettle fibres, she got from this 12 pocket handkerchiefs, 18 ells of checked linen and 12 ells of bed ticking” When Britain cut off the supply of cotton in two world wars, the Germans made not only sandbags but also uniforms from nettle.

The Giant Nettle of Nepal

The nettle yarn I use in my work is Allo from the Himalayan giant stinging nettle which produces fibres amongst the longest found in plants. It occurs naturally in damp woodlands at altitudes between 1,200 and 3000 metres.

The stems and large lobed leaves are covered with stinging hairs. The plant seeds freely and sends up young shoots each year. Harvesting of the allo bark takes place towards the end of the monsoon and goes on until December. Both men and women do the harvesting, cutting only mature stems about 6 inches from the ground to ensure regeneration. The stinging thorns on both stem and leaves makes the cutting of the stem hazardous so the cutters protect their hands with a bundle of cloth which they also use for rubbing off the leaves and thorns.

The ribbons of fibrous bark, separated from the stalk, are tied in bundles and dried in the sun. Traditionally this material is then boiled in wood ash for three hours and left to simmer overnight. The fibres are then soaked in clay which prevents them from sticking together and facilitates spinning which is performed using a hand spindle.

Allo fibres are carried on most journey’s and are spun not only when resting but even along most difficult walks. Allo is traditionally woven by Nepalese women on a back strap loom, mainly during winter when no fieldwork needs to be done. All parts of the loom except the wooden beater are carved from bamboo.In the early 1980’s the nettle weavers from an area in the Kosi Hills (N.E Nepal) decided to expand their range of items and sell their weaving and knitting to dealers in Kathmandu.

The government of Nepal, with the support of the U.K. Overseas Development Administration had initiated research into allo processing and cultivation aimed at increasing rural income. As the plant grows on areas unsuitable for arable crops, cultivation would not compete for land with food crops and could be encouraged along forest edges and rocky slopes.

The weaving centre was built, partly funded by the British Ambassadors Special Fund, and opened for training in 1988; a weaving club was started which grew so much that there were sub clubs at village level. The National Park and Conservation Area Project took over in 1990 promoting the sustainable use of allo, Girardinia diversifolia. Having been grown for centuries in Nepal, it has an increasing role in the economy of the country and its products are now sought after in the west.

This information I gained from Susi Dunsmore who worked with her late husband John Dunsmore organising Kardep, the Kosi Hill Development Scheme in Nepal. She became interested in the nettle production and helped to organise a better system for the finished cloth and garments so that people can improve their earnings. She has written several books on weaving in Nepal.